Samuel Carter Hall (1800-1889), and his wife Anna Maria (1800-1881) compiled a three volume guide to Ireland between 1841-1843. Each chapter is dedicated to a different county. Below is their article on their tour of Longford including a visit to Edgeworthstown and the Edgeworth family.

The inland county of Longford, in the province of Leinster, is bounded on the south and east by that of Westmeath, on the west by that of Roscommon, from which it is separated by the Shannon and Lough Ree, and on the north by the counties of Cavan and Leitrim. It comprises, according to the Ordnance survey, an area of 263,645 acres ; of which 192,506 are cultivated ; the remainder being either mountain and bog, or under water. It is divided into the baronies of Abbeyshrule, Ardagh, Granard, Longford, Moydon, and Rathelme. Its principal towns are Longford, Edgeworthstown, Granard, and Lanesborough. The population in 1821, was 107,570 ; in 1831, 112,558 ; and 115,491 in 1841.

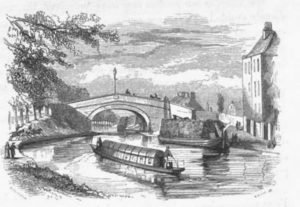

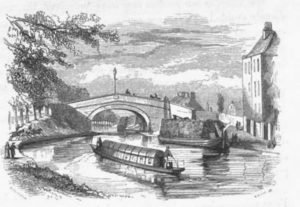

We entered the county by the Royal Canal, voyaging part of the way in one of the Fly boats,” to which we have already made some reference, and to which we recur chiefly in order to supply the reader with a pictorial description of the singular conveyance.” It is long and narrow, covered in as we see it ; and there are two divisions for different classes of passengers. As a mode of travelling, it is exceedingly inconvenient ; there is scarcely space to turn in the confined cabin ; and an outside berth” for more than one is impossible. The guide, or guard, takes his stand at the bow of the boat, and a helmsman controls its motions. It proceeds at a very rapid pace about seven Irish miles an hour drawn by two or three horses, who are made to gallop all the way. There is also a more cumbrous vessel, called a night boat,” which travels at a much slower rate about four miles an hour and always at night. It is large, awkward, and lumbering, and is chiefly used by the peasantry on account of its cheapness.

The county of Longford possesses few features of a distinctive character. It is generally flat ; contains large districts of bog ; and its northern boundaries are overlooked by remarkably sterile mountains. Its principal town of the same name is neat, clean, and well ordered ; it may be distinguished and was so described by the estimable companion with whom we visited it as the best painted town in Ireland ;” for the shops and houses are clean and trim, and partake very little of the negligence and indifference to appearances encountered too generally elsewhere.

Our principal object, in Longford county, was to visit Edgeworthstown, and to avail ourselves of the privilege and advantage of spending some time in the society of Miss Edgeworth. We entered the neat, nice, and pretty town at evening ; all around us bore, as we had anticipated, the aspect of comfort, cheerfulness, good order, prosperity, and their contentment. There was no mistaking the fact, that we were in the neighbourhood of a resident Irish family with minds to devise and hands to effect improvement everywhere within reach of their control.

We have, as our readers may have perceived, throughout this work, studiously avoided all reference to the seats or domains of country gentlemen, except where improvements carried on in particular places excited and deserved general comment. It would have been, however, impossible, within our limited space, to have noticed them all. And we have especially abstained from intruding our own personal acquaintances upon the notice of the reader. We have, as will be readily believed, participated largely in that hospitality for which the country has been always famous. Wherever we have been, we have found a hearty and cordial welcome from all classes ; and every available source of information has been invariably placed within our reach. But we should have ill requited such kind and gratifying attentions, if we had made private individuals topics of public conversation.

Edgeworthstown, however, may almost be regarded as public property. From this mansion has issued so much practical good to Ireland, and not alone to Ireland, but the civilised world, it has been so long the residence of high intellect, industry, well directed genius and virtue, that we violate no duty by requesting our readers to accompany us thither a place that, perhaps, possesses larger moral interest than any other in the kingdom.

[1]

The demesne of Edgeworthstown is judiciously and abundantly planted ; and the dwelling house is large and commodious. We drove up the avenue at evening. It was cheering to see the lights sparkle through the windows, and to feel the cold nose of the house dog thrust into our hands as an earnest of welcome ; it was pleasant to receive the warm greeting of Mrs. Edgeworth; and it was a high privilege to meet Miss Edgeworth in the library, the very room in which had been written the immortal works that redeemed a character for Ireland, and have so largely promoted the truest welfare of human kind. We had not seen her for some years except for a few brief moments and rejoiced to find her in nothing changed ; her voice as light and happy, her laughter as full of gentle mirth, her eyes as bright and truthful, and her countenance as expressive of goodness and loving kindness, as they had ever been.

The library at Edgeworthstown is by no means the reserved and solitary room that libraries are in general. It is large, and spacious, and lofty ; well stored with books, and embellished with those most valuable of all classes of prints the suggestive ; it is also picturesque having been added to so as to increase its breadth the addition is supported by square pillars, and the beautiful lawn seen through the windows, embellished and varied by clumps of trees, judiciously planted, imparts much cheerfulness to the exterior. An oblong table in the centre is a sort of rallying point for the family, who group around it reading, writing, or working ; while Miss Edgeworth, only anxious upon one point, that all in the house should do exactly as they like without reference to her, sits quietly and abstractedly in her own peculiar corner, on the sofa ; her desk, upon which lies Sir Walter Scott’s pen, given to her by him when in Ireland, placed before her upon a little quaint table, as unassuming as possible. Miss Edgeworth’s abstractedness would puzzle the philosophers ; in that same corner, and upon that table, she has written nearly all that has enlightened and delighted the world ; there she writes as eloquently as ever, wrapt up, to all appearance, in her subject, yet knowing by a sort of instinct when she is really wanted in dialogue ; and, without laying down her pen, hardly looking up from her page, she will, by a judicious sentence, wisely and kindly spoken, explain and elucidate, in a few words, so as to clear up any difficulty, or turn the conversation into a new and more pleasing current. She has the most harmonious way of throwing in explanations ; informing without embarrassing. A very large family party assemble daily in this charming room, young and old bound alike to the spot by the strong chords of memory and love. Mr. Francis Edgeworth, the youngest son of the present Mrs. Edgeworth, and, of course, Miss Edgeworth’s youngest brother, has a family of little ones, who seem to enjoy the freedom of the library as much as their elders ; to set these little people right, if they are wrong ; to rise from her table to fetch them a toy, or even to save a servant a journey ; to mount the steps and find a volume that escapes all eyes but her own, and having done so, to find exactly the passage wanted, are hourly employments of this most unspoiled and admirable woman. She will then resume her pen, and what is more extraordinary, hardly seem to have even frayed the thread of her ideas ; her mind is so rightly balanced, everything is so honestly weighed, that she suffers no inconvenience from what would disturb and distract an ordinary writer.

This library also contains a piano ; and occupied, as it is, by some members of the family from morning till night, it is the most unstudied, and yet, withal, from its shape and arrangement, the most inviting to cheerful study the study that makes us more useful both at home and abroad, of any room we have ever entered. We have seen it under many circumstances ; in the morning early very early for London folks, yet not so early but that Miss Edgeworth had preceded us. She is down stairs before seven, and a table heaped with roses upon which the dew is still moist, and a pair of gloves too small for any hands but hers, told who was the early florist ; then, after the flower glasses were replenished, and a choice rose placed by each cup on the breakfast table in the next room, and such of the servants as were Protestants had joined in family worship, and heard a portion of Scripture read, hallowing the commencement of the day ;then when breakfast was ended, the circle met together again in that pleasant room, and daily plans were formed for rides and drives ; the progress of education or the loan fund was discussed, the various interests of their tenants, or the poor, were talked over, so that relief was granted as soon as want was known. It is perhaps selfish to regret that so much of Miss Edgeworth’s mind has been, and is, given to local matters ; but the pleasure it gives her to counsel and advise, and the pure happiness she evidently derives from the improvement of every living thing, is delightful indeed to witness.

But of all hours those of the evening in the library at Edgeworthstown, were the most delightful ; each member of the family contributes, without an effort, to the instruction and amusement of the whole. If we were certain that those of whom we write would never look upon this page if we felt it no outrage on domestic life no breach of kindly confidence to picture each individual of a family so highly gifted, we could fill our number with little else than praise ; but we might give pain and we believe should give pain to this estimable household ; and although Miss Edgeworth is public property, belonging to the world at large, we are forced every now and then to think how the friend we so respect, esteem, and love, would look if we said what let us say as little as we will she would deem, in her ingenuous and unaffected modesty, too much ; yet we owe it to the honour and glory of Ireland not to say too little.

It was indeed a rare treat to sit, evening after evening, by her side, turning over portions of the correspondence kept up with her, year after year, by those I mighty ones,” who are now passed away, but whose names will survive with hers, who, God be thanked ! is still with us ; to see her enthusiasm unquenched ; to note the playfulness of a wit that is never ill-natured ; to observe how perfectly justice and generosity are blended together in her finely balanced mind ; to see her kindle into warm defence of whatever is oppressed, and to mark her indignation against all that is unjust or untrue. We have heard Miss Edgeworth called cold,” we can imagine how those who know her must smile at this ; those who have so called her, have never seen the tears gush from her eyes at a tale or an incident of sorrow, or heard the warm genuine laugh that bursts from a heart, the type of a genuine Irish one, touched quickly by sorrow or by joy. Never, never shall we forget the evenings spent in that now far away room, stored with the written works, and speaking memories, of the past, and rendered more valuable by the unrestrained conversation of a highly educated and self thinking family.

Miss Edgeworth is a living proof of her own admirable system ; she is all she has endeavoured to make others ; she is TRUE , fearing no colours, yet tempering her mental bravery by womanly gentleness delighting in feminine amusements in the plying of her needle, in the cultivation of her flowers ; active, enduring of a most liberal heart ; understanding the peasantry of her country perfectly, and while ministering to their wants, careful to inculcate whatever lesson they most need ; of a most cheerful nature keeping actively about from half past six in the morning until eleven at night first and last in all those offices of kindness that win the affections of high and low ; her conversational powers unimpaired, and enlivening all by a racy anecdote or a quickness at repartee, which always comes when it is unexpected.

It is extraordinary that a person who has deserved and is treated with so much deference by her own family, should assume positively no position. Of course, it is impossible to converse with her without feeling her superiority; but this is your feeling, not her demand. She has a clearness in conversation that is exceedingly rare ; and children prefer it at once they invariably understand her. One advantage this distinguished woman has enjoyed above all her cotemporaries, two indeed, for we cannot call to mind any one who has had a father so capable of instructing and directing ; but Miss Edgeworth has enjoyed another blessing. She never wrote for bread ! She was never obliged to furnish a bookseller with so many pages at so much per sheet. She never received an order for a quire of Irish pathos,” or a ream of Irish wit.” She was never forced to produce humour when racked by pain, nor urged into the description of misery, by thinking over what she had herself endured ; this has been a great blessing. She has not written herself out, which every author, who has not an independence, must do, sooner or later.

It is to their high honour that women were the first to use their pens in the service of Ireland we do not mean politically but morally. For a number of years, a buffoon, a knave, and an Irishman, were synonymous terms in the novel, or on the stage. Abroad, to be met with in every country, and in the first society in Europe, were numberless Irishmen, whose conduct and character vindicated their country, and who did credit to human nature ; but in England, more particularly, such were considered as exceptions to the general rule, and the insulting jibe and jeer were still directed against the mere Irish ;” the oppressed peasant at home and abroad was considered as nothing beyond a born thrall ;” and, despite the eloquence of their Grattans and Sheridans, the high standing taken by their noblemen and gentlemen in the pages of history, when an Irish gentleman in everyday life was found what he ought to be, his superiority was too frequently referred to with the addition of an insulting comment, I though he is an Irishman.” When this prejudice was at its height, two women, with opposite views and opposite feelings on many subjects, but actuated by the same ennobling patriotism, rose to the rescue of their country Miss Owenson by the vivid romance, and Miss Edgeworth by the stern reality of portraiture, forcing justice from an unwilling jury ! spreading abroad the knowledge of the Irish character, and portraying, as they never had been portrayed before, the beauty, generosity, and devotion, of Irish nature it was a glorious effort, worthy of them and of the cause both planted the standard of Irish excellence on high ground, and defended it, boldly and bravely, with all loyalty, in accordance with their separate views.

We rejoice at this opportunity of expressing our respect and affection for Miss Edgeworth; and tender it with a whole heart. If we have ourselves been useful in communicating knowledge to young or old if we have succeeded in our hopes of promoting virtue and goodness and, more especially, if we have, even in a small degree, attained our great purpose of advancing the welfare of our country we owe, at least, much of the desire to do all this, to the feelings derived in early life from intimacy with the writings of Miss Edgeworth ; writings which must have formed and strengthened the just and upright principles of tens of thousands ; although comparatively few have enjoyed the high privilege of treading no matter at how large a distance in her steps. Much, too, we have owed to this estimable lady in after life. When we entered upon the uncertain, anxious, and laborious career of authorship, she was among the first to cheer us on our way; to bid us God speed ;” and to anticipate that prosperity of which we would speak only in terms of humble but grateful thankfulness.

The county of Longford has been rendered famous by another immortal name. It contains the birthplace of Oliver Goldsmith : he was born at Pallas, on the 10th of November, 1728.

[2] The village of Pallas, Pallice, or Pallasmore, about two miles from the small town of Ballyymahon, is now a collection of mere cabins ; the house in which the poet was ushered into life has been long since levelled with the ground ; we could discover no traces of it, nor could we perceive in the neighbourhood any objects to which the poet might have been supposed to have made reference in after life. The village of Lissoy, generally considered the place of his birth, but certainly the Seat of his youth, when every sport could please, is in the county of Westmeath, a short distance from the borders of Longford, on the high road from Edgeworthstown to Athlone, from which it is distant about six miles. The Rev. Charles Goldsmith appears to have removed to this place soon after the birth of Oliver, about the year 1730, when he was appointed to the rectory of Kilkenny West : here the childish and boyish days of the poet were passed, and here his brother the Rev. Henry Goldsmith continued to reside after his father’s death, and was residing when the poet dedicated to him his poem of ‘ The Traveller.

The village of Lissoy, now and for nearly a century known as Auburn, and so marked on the maps,” stands on the summit of a hill. We left our car to ascend it, previously, however, visiting, at its base, the busy mill,” the wheel of which is still turned by the water of a small rivulet, converted now and then by rains into a sufficient stream. It is a mere country cottage, used in grinding the corn of the neighbouring peasantry, and retains many tokens of age. Parts of the machinery are no doubt above a century old, and probably are the very same that left their impress on the poet’s memory. As we advanced, other and more convincing testimony was afforded by the localities. A tall and slender steeple, distant a mile perhaps, even today indicates the decent church that tops the neighbouring hill, and is seen from every part of the adjacent scenery. To the right, in a miniature dell, the pond exists ; and while we stood upon its bank, as if to confirm the testimony of tradition, we heard the very sounds which the poet describes “The noisy geese that gabbled over the pool.”

On the summit of the ascent, close beside the village alehouse, where nutbrown draughts inspired,” a heap of cemented stones points out the site of the spreading tree “The hawthorn bush, with seats beneath the shade For talking age and whispering lovers made.”

The hawthorn was flourishing within existing memories ; strengthened and sustained by this rude structure around it a plan of preserving trees very common throughout the district ; but unhappily, about forty or fifty years ago, it was I knocked down by a cart,” strange to say, laden with apple trees, which some carter was conveying into Ballymahon ; one of them struck against the aged and venerable thorn, and levelled it with the earth.

[3] There it remained until, bit by bit, it was removed by the curious as relics : the root, however, is still preserved by a gentleman of Athlone. On the opposite side of the road, and immediately adjoining the decent public,” is a young and vigorous sycamore, upon which now hangs the sign of The Pigeons ;” the little inn is still so called, and gives its name, indeed, to the village ; for, upon conversing with two or three of the peasantry, old as well as young, we found they did not recognise their home either as Lissoy or Auburn ; but on asking them plainly how they called it, we were answered, The Pigeons, to be sure.”

[4]

Nevertheless it was pleasant to be reminded even by a modern successor to the spreading tree,” that we stood near yonder thorn that lifts its head on high, where once the signpost caught the passing eye.”

The public” differs little from the generality of wayside inns in Ireland. The kitchen,” if so we must term the apartment first entered, contained the usual furniture: a deal table, a few chairs, a settle,” and the potato pot beside the hob, adjacent to which were a couple of bosses, or rush seats. There was a parlour adjoining, and a floor above ; but we may quote and apply, literally, a passage from the ‘ Deserted Village :

” Imagination fondly stoops to trace the parlour splendours of that festive place ; The whitewashed wall, the nicely sanded floor, The varnished clock that clicked behind the door”

objects that we suspect never existed at any period, except in the imagination of the poet ; being as foreign to the locality as the nightingale,” to which he alludes in a subsequent passage a bird unknown in Ireland.

[5]

The old inn, however, was removed long ago ; and the present building, although sufficiently decent,” gave ample evidence that it was not a house of call ;” there was no whiskey, either in its cellars or its bottles, and the nutbrown draughts” that were to solace greybeard mirth” and smiling toil,” and to stimulate village statesmen,” must have been composed of tea the only beverage which the inn afforded.

[6]

The remains of the Parsonage House stand about a hundred yards from The Pigeons.” About fifty years ago, we were told, the road was lined at either side by lofty elm trees, which formed a shaded walk completely arched they used to lap across,” as we were informed by one of the peasants. They have all perished, except a few juvenile successors, planted between the entrance gate and the dwelling. It is a complete ruin. The roof fell about twenty five years ago, if our informant, a neighbouring peasant, stated correctly; it was always thatched, according to his account, and up to that period a gentleman had lived in it.” It must have been a modest mansion” of no great size. The front,” according to Mr. Prior, extends, as nearly as could be judged by pacing it, sixty eight feet by a depth of twenty four ; it consisted of two stories, of five windows in each.” The length was increased by the addition of the school room”at least tradition so describes a chamber, the walls of which are remarkably thick, which adjoins the south gable ; it is now used as a ball alley. Several stone cupboards,” as it were, are still to be seen in the walls, where, we learn from the same authority tradition the boys used to keep their books. At the back of the building, the remains of an orchard are still clearly discernible ; there are no garden flowers” growing wild” about it ; but there exist a few torn shrubs,” that even now disclose” the place where

The village preacher’s modest mansion rose.”

Of the schoolmaster,” whose name is said to have been Paddy Burns,” whom the traveller in America” recollected well, and whom he describes as indeed a man severe to view,” we could learn nothing more than the fact, that Byrne not Paddy but Thomas, and not Burns but Byrne, as stated by Mr. Prior was a schoolmaster of whom old people would still be talking.” It appears, however, that when Oliver was about three years old, his earliest instructress was a woman named Delap ; who, almost with her last breath, boasted of being the first person who had put a book into Oliver’s hands.” According to her account, he was a remarkably dull child, impenetrably stupid ;” and for several subsequent years he was looked upon by his contemporaries and schoolfellows, as a stupid heavy blockhead, little better than a fool, whom every one made fun of ;” but, at the same time, docile, diffident, and easily managed.”

[7]

Byrne, under whose charge he was placed when about six years old, was a singular character : he had been a soldier ; and was wont to entertain his scholars with stories of his adventures, swaying his ferule, To show how fields were won.”

Much of the wandering and unsettled mind of the poet is attributed to the sort of wild and rambling education he received under the roof of the noisy mansion” of Mr. Byrne ; and there can be little doubt that the tales and legends, of which the Irish peasantry have been always the fertile producers, gave to his genius that peculiar bias which determined his after career.

Goldsmith left the neighbourhood of Lissoy for a school at Athlone, and subsequently for another at Edgeworthstown, from which he removed to the University ; and on the 11th of June, 1744, when sixteen years of age, he was entered of Trinity College, Dublin.

Whether he ever afterwards returned to Lissoy is very questionable. His brother, with whom he frequently corresponded, continued there as the country clergyman” A man he was to all the country dear, And passing rich with forty pounds a year ;” who spent his days remote from strife,” and of whom the world knew nothing. It is probable, however, that Oliver visited the parsonage once or twice during his collegiate course ; that in after life he longed to do so, we have undoubted evidence : In all my wanderings round this world of care, In all my griefs and God has given my share still had hopes, my latest hours to crown, Amidst these humble bowers to lay me down.”

The circumstances under which he pictured Sweet Auburn” as a deserted village, remain in almost total obscurity. If his picture was in any degree drawn from facts, they were, in all likelihood, as slender as the materials which furnished his description of the place, surrounded by all the charms which poetry can derive from invention. Some scanty records, indeed, exist to show, that about the year 1838 there was a partial clearing” of an adjoining district Amidst thy boughs the tyrant hand is seen ;” and this circumstance might have been marked by some touching episodes which left a strong impress upon the poet’s mind ; but the poem bears ample evidence, that, although some of the scenes depicted there had been stamped upon his memory, and had been subsequently called into requisition, it is so essentially English in all its leading characteristics2scarcely one of the persons introduced, the incidents recorded, or the objects described, being in any degree Irish the STORY must be either assigned to some other locality, or traced entirely to the creative faculty of the poet.

NOTES

[1]

The Abbé Edgeworth was uncle to Richard Lovell Edgeworth, the father of Maria Edgeworth. Mr. Edgeworth’s residence abroad had enlarged a mind of far more than ordinary capacity. He had passed much time in England, and did not feel disposed to suffer things to go on in the wrong” in Ireland because they had been always so ;” once settled upon his estate in Longford, he laboured with zeal, tempered by patience and forbearance, among a tenantry dreading change, and too frequently considering improvements” as insults” to their ancestors and injustice to themselves. Those who desire to ascertain the value and intelligence of this enterprising gentleman, who, in all good respects, was far beyond the age in which he lived, will be amply rewarded by the perusal of his ‘ Life, commenced by himself and finished by his daughter. It is curious to note how many persons, unknown to themselves, have been working out ideas concerning education, and other matters which he originated, and which, in many instances, were, at the time he promulgated them, rejected as visionary, or at least impracticable. The time was not come ; but he foresaw it. He knew the future by his knowledge of the present and the past. His capacious mind was not content with a mere speculative opinion ; but when he had established a theory, he put it in practice : thus, at an advanced age, which is supposed to require especial repose, he undertook the drainage of bogs, and was as anxiously engaged in absolute labour as if he had been only five and twenty. In early life, he devoted considerable time to mechanics, and his inventions have been acknowledged with due honour2and yet not with all the honour they deserved. It will excite no surprise, that a man so much in advance of the age, should have been occasionally misunderstood by his own class ; yet he outlived prejudice, and his children have seen his memory respected alike by rich and poor, and his name classed among the benefactors to mankind. One proof of the power and success of his mechanical genius is pointed out with much exultation by the peasantry to the stranger2the spire of the church, where so many of the Edgeworth family are interred, is of metal, and was drawn up and fixed in its elevated position in the space of a few minutes.

Maria Edgeworth was not born in Ireland she entered the world she has helped to regenerate during her parents’ residence in Oxfordshire and did not go to Ireland until she was twelve years old.

[2]

The honour has been disputed by no fewer than four places in as many counties Drumsna, in Leitrim ; Lissoy, in Westmeath ; Ardnagan, in Roscommon ; and Pallas, in Longford. The question, however, may be considered as settled by Mr. Prior (‘ Life of Goldsmith,Г) who examined the Family Bible, now in the possession of one of the descendants, in which was the following entry of the birth of Oliver, the third son and sixth child of the Rev. Charles and Ann Goldsmith :2

Oliver Goldsmith was born at Pallas, Nov. ye 10th, 17_.” The marginal portion of the leaf having been unluckily torn away, the two last figures of the century are lost ; ” the age of the poet is, however, sufficiently ascertained by the recollection of his sister, and by his calling himself, when writing from London, in 1759, thirtyone.”

In the epitaph, written by Dr. Johnson, and placed on Goldsmith’s monument in Westminster Abbey, are these words :

” Natus in Hibernia, Fornia

Lonfordiensis, in loco cui nomen Pallas.”

Here, however, the day and year of his birth are recorded as Nov. 29, 1731: and in the statement given by Mrs. Hodson, elder sister of the poet, to Bishop Percy, the day named is Nov. 29. It is clear from other documents also, that his birthplace was Lissoy. The family was of English descent; and appears to have furnished clergymen to the Established Church for several generations. One of them, the Rev. John Goldsmith, parson of Brashoul” (Burrishoole), in the county of Mayo, had a narrow and singular escape during the Rebellion of 1641. From the examination of Mr. Goldsmith, it appears that the Protestant inhabitants of Castleburre (Castlebar), had been promised safe conduct to Galway by I the Lord of Mayo,” Viscount Bourke, a Roman Catholic, married to a Protestant ; previously to setting out, however, Mr. Goldsmith was detached from the party, no doubt in order to save his life, under the pretence of attending upon the lady. At Shrule, they were transferred to the I guardianship” of Edmond Bourke, a namesake and relative of the Lord of Mayo. When, according to the evidence of Mr. Goldsmith, I Bourke drew his sword, directing the rest what they should do, and began to massacre those Protestants ; and, accordingly, some were shot to death, some stabbed with skeins, some run through with pikes, some cast into the water ; and the women, that were stripped naked, lying upon their husbands to save them, were run through with pikes.” The Rev. Charles Goldsmith, the father of the poet, married Ann, daughter of the Rev. Oliver Jones, master of the Diocesan school at Elphin. Both were poor when they began the world ; and the Rev. Mr. Green, uncle of Mrs. Goldsmith, provided them with a house at Pallas, where they lived for a period of twelve years ; and where six of their children were born2the remaining three having been born at Lissoy. The list of their children, as copied by Mr. Prior, from the Family Bible referred to, cannot fail to interest the reader. The entry stands thus :

Charles Goldsmith of Ballyoughter was married to Mrs. Ann Jones, ye 4th of May, 1718.

Margaret Goldsmith was born at Pallismore, in the county of Longford, ye 22d August, 1719.

Catherine Goldsmith, born at Pallas, ye 13th January, 1721.

Henry Goldsmith was born at Pallas, February 9th, 17_.

Jane Goldsmith was born at Pallas, February 9th, 17_.

Oliver Goldsmith was born at Pallas, November 10th, 17_.

Maurice Goldsmith was born at Lissoy, in ye county of Westmeath, 7th of July, 1736.

Charles Goldsmith, junior, born at Lissoy, August 16th, 1737.

John Goldsmith, born at Lissoy, ye 23d of (month obliterated) 1740.”

[3]

Mr. Prior quotes an anecdote I told by a traveller (Davis) some years ago, in the United States.” Mr. Best, an Irish clergyman, informed this I traveller,” that he was once riding with Brady, titular Bishop of Ardagh, when he observed, I Ma foy, Best, this huge bush is mightily in the way ; I will order it to be cut down.” I What, sir,” said Best, I cut down GoldsmithГs hawthorn bush, that supplies so beautiful an image in the ‘ Deserted Village !Г I Ma foy,” exclaimed the bishop, I is that the hawthorn bush ? Then ever let it be sacred from the edge of the axe ; and evil be to him that would cut from it a branch !”

[4]

The name of the public house called I The Pigeons” in the time of Goldsmith, as well as at present does not occur in the poem of the ‘ Deserted Village ; but it is the name given to the inn in which Tony Lumpkin plays his pranks The Three Pigeons”and where he misleads the hero of the comedy, ‘ She Stoops to Conquer, into mistaking the mansion of Squire Hardcastle for a tavern. There is little doubt that such an incident did actually happen to the poet himself ; and that many other of his early adventures were subsequently introduced into his fictitious narratives. We heard from Capt. E22, a descendant of the poet, a story that will call to mind the leading occurrence in ‘ The Vicar of Wakefield. A Mr. J22, the heir to a considerable property in Westmeath, was travelling to Dublin on horseback, (as usual in those days), attended by his natural brother, who acted as his servant. On the way they agreed to exchange clothes and positions ; and when this was effected, they called at the dwelling of Mr. Goldsmith, where the natural brother, in his assumed character, paid his addresses to the clergyman’s sister, to whom he was soon afterwards married ; and until the marriage had taken place, the cheat was not discovered.

[5]

There is, however, some authority for the existence at “The Pigeons” of

“The pictures placed for ornament and use,

The twelve good rules, the royal game of goose.”

Mr. Brewer states, that ” a lady from the neighbourhood of Portglenone, in the county of Antrim, visited Lissoy in the summer of 1817, and was fortunate enough to find in a cottage adjoining the alehouse, the identical print of the ‘twelve good rules’ which ornamented the rural tavern, along with ‘ the royal game of goose. I We were told that the I old original” signYboard lay, not many years ago, in an outhouse, and was removed thence to the mansion 2Auburn House2of Mr. Hogan, who is said to be in possession of the chair and reading desk of Goldsmith’s brother, the clergyman. Mr. Prior observes, that I this gentleman has used all his influence to preserve, from the ravages of time and passing depredators, such objects and localities as seem to mark allusions to the poem.” We confess, however, that we could find nothing I preserved,” except the things which even Time itself could not destroy.

[6]

The American authority already quoted it is to be regretted that the date of the visit is not indicated states, that the inn was then kept by I a woman called Walsey Kruse.” The oldest existing inhabitant of the neighbourhood bears the same name Kruse. He told us that his age was above ninety ; but he had little or no information to afford us. He recollected, he said, perfectly, the clergyman, Mr. Goldsmith a nice, kind little gentleman he was,” added the old man. Upon inquiring if he had any recollection of I the poet” a title very well understood by the humbler Irish2his answer was, Oh no, I never knew the man at all, at all.” I Did you ever hear of him ?” Oh yes ; plenty of the quality come to see the place.” Do you remember his ever having been here himself ?” No ; I never see him at all, nor any of the neighbours.” We could obtain nothing more the old man neither drank, smoked, nor took snuff ; and we had no stimulus to rouse his dormant energies, as he sat listlessly by the fire side of his cottage.

[7]

Connected with this period of his life may be noticed an anecdote, inserted in Mr. Graham’s Statistical Account of Shruel,” on the authority of a direct descendant of the Rev. Henry Goldsmith. Goldsmith was always plain in his appearance, but when a boy, and immediately after suffering heavily with the smallpox, he was particularly ugly. When he was about seven years old, a fiddler, who reckoned himself a wit, happened to be playing to some company in Mrs. GoldsmithГs house ; during a pause between the country-dances, little Oliver surprised the party by jumping up suddenly, and dancing round the room. Struck with the grotesque appearance of the ill favoured boy, the fiddler exclaimed, ‘ Aesop !’ and the company burst into laughter, when Oliver turned to them with a smile, and repeated the following lines:

‘ Heralds proclaim aloud, all saying,

See Aesop dancing, and his monkey playing. ”

Ireland, its scenery, character and history (1911) Author : Hall, S.C. (Samuel Carter), 1800Y1889 ; Hall, S. C., Mrs., 1800Y1881 Volume : 6 Subject : Ireland 2 Description and travel Publisher : Boston : F. A. Niccolls Language : English Digitizing sponsor : MSN Book contributor : Kelly 2 University of Toronto Collection : kellylibrary; toronto

Source : Internet Archive http://archive.org/details/irelanditsscener06halluoft