Despite her work as a novelist, short story writer and playwright, Maria Edgeworth was also a prolific letter writer. Therefore she wrote to family and friends about events that they witnessed and lived through. As a result Maria left us letters on how the Edgeworths were experiencing the 1798 rebellion.

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was one of the main events leading to the passing of the Acts of Union 1800. Republican forces were rioting against British rule in Ireland. These forces were organised by the Society of United Irishmen and supported by the majority Catholic population. But even with the help of a French expeditionary force and some victories on the way, the rebellion was quickly suppressed.

Also many of Maria’s letters have been collected into book form. Meanwhile some of these can be purchased, others are available from the Project Gutenburg website and can be downloaded. Or you can download the Kindle version here

In the article below Maria Edgeworth writes about how the Edgeworths experienced the 1798 rebellion. For the purposes of this article I have done some editing of the content to amalgamate all the separate bits together.

The Mrs Edgeworth mentioned is Frances Beaufort, Richard Lovell Edgeworth‘s fourth wife whom he’d married in May 1798.

When we set off from the church door for Edgeworthstown, the rebellion had broken out in many parts of Ireland. Soon after we had passed the second stage from Dublin, one of the carriage wheels broke down. Mr. Edgeworth went back to the inn, then called the Nineteen-mile House, [Footnote: Now Enfield: a railway station.] to get assistance. Very few people were to be found, and a woman who was alone in the kitchen came up to him and whispered, “The boys (the rebels) are hid in the potato furrows beyond.” He was rather startled at this intelligence, but took no notice. He found an ostler who lent him a wheel, which they managed to put on, and we drove off without being stopped by any of the boys. A little further on I saw something very odd on the side of the road before us. “What is that?”—”Look to the other side—don’t look at it!” cried Mr. Edgeworth; and when we had passed he said it was a car turned up, between the shafts of which a man was hung—murdered by the rebels.

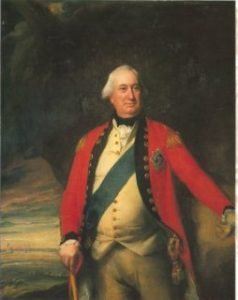

Hitherto all has been quiet in our county, and we know nothing of the dreadful disturbances in other parts of the country but what we see in the newspapers. I am sorry my uncle and Richard were obliged to leave you and my dear aunt, as I know the continual state of suspense and anxiety in which you must live while they are away. I fear that we may soon know by experience what you feel, for my father sees in to-night’s paper that Lord Cornwallis is coming over here as Lord-Lieutenant; and he thinks it will be his duty to offer his services in any manner in which they can be advantageous.

We have this moment learned from the sheriff of this county, Mr. Wilder, who has been at Athlone, that the French have got to Castlebar. They changed clothes with some peasants, and so deceived our troops. They have almost entirely cut off the carbineers, the Longford militia, and a large body of yeomanry who opposed them. The Lord-Lieutenant is now at Athlone, and it is supposed that it will be their next object of attack. My father’s corps of yeomanry are extremely attached to him, and seem fully in earnest; but, alas! by some strange negligence their arms have not yet arrived from Dublin. My father this morning sent a letter by an officer going to Athlone, to Lord Cornwallis, offering his services to convey intelligence or reconnoitre, as he feels himself in a most terrible situation, without arms for his men, and no power of being serviceable to his country. We who are so near the scene of action cannot by any means discover what number of the French actually landed: some say 800, some 1800, some 18,000, some 4000. The troops march and countermarch, as they say themselves, without knowing where they are going, or for what.

We are all safe and well, my dearest aunt, and have had two most fortunate escapes from rebels and from the explosion of an ammunition cart. Yesterday we heard, about ten o’clock in the morning, that a large body of rebels, armed with pikes, were within a few miles of Edgeworthstown. My father’s yeomanry were at this moment gone to Longford for their arms, which Government had delayed sending. We were ordered to decamp, each with a small bundle: the two chaises full, and my mother and Aunt Charlotte on horseback. We were all ready to move, when the report was contradicted: only twenty or thirty men were now, it was said, in arms, and my father hoped we might still hold fast to our dear home.

Two officers and six dragoons happened at this moment to be on their way through Edgeworthstown, escorting an ammunition cart from Mullingar to Longford: they promised to take us under their protection, and the officer came up to the door to say he was ready. My father most fortunately detained us: they set out without us. Half an hour afterwards, as we were quietly sitting in the portico, we heard—as we thought close to us—a clap of thunder, which shook the house. The officer soon afterwards returned, almost speechless; he could hardly explain what had happened. The ammunition cart, containing nearly three barrels of gunpowder, packed in tin cases, took fire and burst, halfway on the road to Longford. The man who drove the cart was blown to atoms—nothing of him could be found; two of the horses were killed, others were blown to pieces and their limbs scattered to a distance; the head and body of a man were found a hundred and twenty yards from the spot. Mr. Murray was the name of the officer I am speaking of: he had with him a Mr. Rochfort and a Mr. Nugent. Mr. Rochfort was thrown from his horse, one side of his face terribly burnt, and stuck over with gunpowder. He was carried into a cabin; they thought he would die, but they now say he will recover. The carriage has been sent to take him to Longford.

I have not time or room, my dear aunt, to dilate or tell you half I have to say. If we had gone with this ammunition, we must have been killed. An hour or two afterwards, however, we were obliged to fly from Edgeworthstown. The pikemen, three hundred in number, actually were within a mile of the town. My mother, Aunt Charlotte, and I rode; passed the trunk of the dead man, bloody limbs of horses, and two dead horses, by the help of men who pulled on our steeds we are all safely lodged now in Mrs. Fallon’s inn.

Before we had reached the place where the cart had been blown up, Mr. Edgeworth suddenly recollected that he had left on the table in his study a list of the yeomanry corps, which he feared might endanger the poor fellows and their families if it fell into the hands of the rebels. He galloped back for it—it was at the hazard of his life—but the rebels had not yet appeared. He burned the paper, and rejoined us safely. The landlady of the inn at Longford did all she could to make us comfortable, and we were squeezed into the already crowded house.

Mrs. Billamore, our excellent housekeeper, we had left behind for the return of the carriage which had taken Mr. Rochfort to Longford; but it was detained, and she did not reach us till the next morning, when we learned from her that the rebels had not come up to the house. They had halted at the gate, but were prevented from entering by a man whom she did not remember to have ever seen; but he was grateful to her for having lent money to his wife when she was in great distress, and we now, at our utmost need, owed our safety and that of the house to his gratitude. We were surprised to find that this was thought by some to be a suspicious circumstance, and that it showed Mr. Edgeworth to be a favourer of the rebels!

An express arrived at night to say the French were close to Longford: Mr. Edgeworth undertook to defend the gaol, which commanded the road by which the enemy must pass, where they could be detained till the King’s troops came up. He was supplied with men and ammunition, and watched all night; but in the morning news came that the French had turned in a different direction, and gone to Granard, about seven miles off; but this seemed so unlikely, that Mr. Edgeworth rode out to reconnoitre, and Henry went to the top of the Court House to look out with a telescope. We were all at the windows of a room in the inn looking into the street, when we saw people running, throwing up their hats and huzzaing. A dragoon had just arrived with the news that General Lake’s army had come up with the French and the rebels, and completely defeated them at a place called Ballinamuck, near Granard.

But we soon saw a man in a sergeant’s uniform haranguing the mob, not in honour of General Lake’s victory, but against Mr. Edgeworth; we distinctly heard the words, “that young Edgeworth ought to be dragged down from the Court House.” The landlady was terrified; she said Mr. Edgeworth was accused of having made signals to the French from the gaol, and she thought the mob would pull down her house; but they ran on to the end of the town, where they expected to meet Mr. Edgeworth. We sent a messenger in one direction to warn him, while Maria and I drove to meet him on the other road. We heard that he had passed some time before with Major Eustace, the mob seeing an officer in uniform with him went back to the town, and on our return we found them safe at the inn. We saw the French prisoners brought in in the evening, when Mr. Edgeworth went after dinner with Major Eustace to the barrack. Some time after, dreadful yells were heard in the street: the mob had attacked them on their return from the barrack–Major Eustace being now in coloured clothes, they did not recognise him as an officer. They had struck Mr. Edgeworth with a brickbat in the neck, and as they were now, just in front of the inn, collaring the major, Mr. Edgeworth cried out in a loud voice, “Major Eustace is in danger.” Several officers who were at dinner in the inn, hearing the words through the open window, rushed out sword in hand, dispersed the crowd in a moment, and all the danger was over. The military patrolled the streets, and the sergeant who had made all this disturbance was put under arrest. He was a poor, half-crazed fanatic.

The next day, the 9th of September, we returned home, where everything was exactly as we had left it, all serene and happy, five days before–only five days, which seemed almost a lifetime, from the dangers and anxiety we had gone through.

You will rejoice, I am sure, my dear Sophy, to see by the date of this letter that we are safe back at Edgeworthstown. The scenes we have gone through for some days past have succeeded one another like the pictures in a magic-lantern, and have scarcely left the impression of reality upon the mind. It all seems like a dream, a mixture of the ridiculous and the horrid. “Oh ho!” says my aunt, “things cannot be very bad with my brother, if Maria begins her letters with magic-lantern and reflections on dreams.”

When we got into the town this morning we saw the picture of a deserted, or rather a shattered village–many joyful faces greeted us at the doors of the houses–none of the windows of the new houses in Charlotte Row were broken: the mob declared they would not meddle with them because they were built by the two good ladies, meaning my aunts.

Last night my father was alarmed at finding that both Samuel Essington and John, [Footnote: John Jenkins, a Welsh lad; both he and Samuel thought better of it and remained in the service.] who had stood by him with the utmost fidelity through the Longford business, were at length panic-struck: they wished now to leave him. Samuel said: “Sir, I would stay with you to the last gasp, if you were not so foolhardy,” and here he cried bitterly; “but, sir, indeed you have not heard all I have heard. I have heard about two hundred men in Longford swear they would have your life.” All the town were during the whole of last night under a similar panic, they were certain the violent Longford yeomen would come and cut them to pieces.

Enclosed I send you a little sketch, which I traced from one my mother drew for her father, of the situation of the field of battle at Ballinamuck, it is about four miles from The Hills. My father, mother, and I rode to look at the camp; perhaps you recollect a pretty turn in the road, where there is a little stream with a three-arched bridge: in the fields which rise in a gentle slope, on the right-hand side of this stream, about sixty bell tents were pitched, the arms all ranged on the grass; before the tents, poles with little streamers flying here and there; groups of men leading their horses to water, others filling kettles and black pots, some cooking under the hedges; the various uniforms looked pretty; Highlanders gathering blackberries. My father took us to the tent of Lord Henry Seymour, who is an old friend of his; he breakfasted here to-day, and his plain English civility, and quiet good sense, was a fine contrast to the mob, etc. Dapple, [Footnote: Maria Edgeworth’s horse.] your old acquaintance, did not like all the sights at the camp as well as I did.

My father went to Dublin the day before yesterday, to see Lord Cornwallis about the Court of Enquiry on the sergeant who harangued the mob. About one o’clock to-day Lovell returned from the Assizes at Longford with the news, met on the road, that expresses had come an hour before from Granard to Longford, for the Reay Fencibles, and all the troops; that there was another rising and an attack upon Granard: four thousand men the first report said, seven hundred the second. What the truth may be it is impossible to tell, it is certain that the troops are gone to Granard, and it is yet more certain that all the windows in this house are built halfway up, guns and bayonets dispersed by Captain Lovell in every room. The yeomanry corps paraded to-day, all steady: guard sitting up in house and in the town to-night.

All alive and well. A letter from my father: he stays to see Lord Cornwallis on Friday. Deficient arms for the corps are given by Lord Castlereagh.

The sergeant was to have been tried at the next sessions, but he was by this time ashamed and penitent, and Mr. Edgeworth did not press the trial, but knowing the man was, among his other weaknesses, very much afraid of ghosts, he said to him as he came out of the Court House, “I believe, after all, you had rather see me alive than have my ghost haunting you!”

The best way to keep in touch and to be aware of our events

Don’t forget to confirm your subscription in the Email we just sent you!

Please pre-book your visit over Christmas and New Year at least 24h in advance via Email or Online booking.

MondayClosed

Tuesday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Wednesday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Thursday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Friday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Saturday11:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Sunday11:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Adult €7.50

Children 10 to 16 €3

2 Adults & 2 Children €15

Adult is 16 years+

Family Ticket is 4 family members together

Children under ten are free but must be accompanied by an Adult

This project was assisted by Longford Local Community Development Committee, Longford Community Resources Clg. and Longford County Council through the LEADER Programme 2023 -2027 which is part-financed by the EU, “The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in rural areas” and the Department of Rural & Community Development

The Maria Edgeworth Centre is operated under the direction of the Edgeworthstown District Development Association (EDDA) – a Not for Profit Voluntary Community based registered charity Reg:223373. Registered Charity Number 20101916

© 2023 Maria Edgeworth Centre – All Rights Reserved