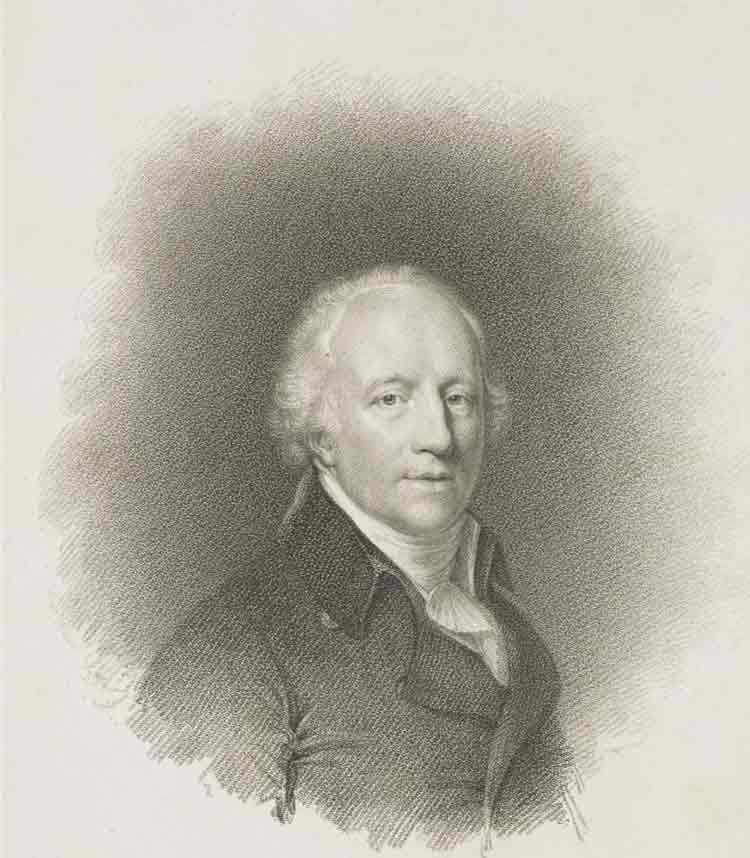

The first member of the family we meet is Richard Lovell Edgeworth, father of Maria. Born in 1744, he survived four wives, and had twenty-two children before dying, aged 73, in 1817.

He was a liberal both in thought and in politics. He was in full sympathy with the eighteenth century enlightenment in science and belief in scientific method, in industrial progress and in educational thinking. He was a friend on the leading scientists and thinkers of the day – such as Erasmus Darwin, Sir Humphrey Davy, James Watt. [Add link to Lunar Society article/images here]

Distinguished as an inventor, he turned his wider-ranging inventive genius to such diverse objects as architecture and town planning, mechanical loaders, carts and carriages with springs, railroad tracks for the transport of peat. He designed and built the spire in the Parrish Church of Edgeworthstown. His architectural skill was in evidence at Pakenham Hall, particularly in the installation of an ingenious domestic heating system.

He was a pioneer of modern techniques of road construction; and it is a rather unfair accident of history that a less brilliant and successful contemporary, the Scotsman, Macadam, should have had his name perpetuated in road-making vocabulary, though Edgeworth did much more to merit that honour. Edgeworth did very important pioneering studies and experiments in telegraphy, and it was obscurantist on the part of the British Government of the time, not to implement his plans for a telegraphic communications system in Ireland before the end of the eighteenth century.

In the sphere of bogland development, Edgeworth remarkably anticipated the work, which had to wait more than a century after his death for full implementation by Bord na Mona. In 1808, the then Chief Secretary, Sir Arthur Wellesley, proposed the setting up of a commission to explore the possibilities of utilisation of the bogs of Ireland. A bill to this effect was introduced in the British Parliament in the following year. The commission was set up and began its investigations immediately.

Edgeworth was invited to act as one of the engineers to the commission. Although now a man of 65 and in failing health, he accepted and threw himself into the work with extraordinary energy declaring, characteristically, that “he could only die, and he would rather die doing something than doing nothing.” He was convinced of the great contribution the bogs could make to the economic prosperity of Ireland. He began by planning a survey of 35,000 acres of bogland on Co. Longford and adjacent areas of Co. Meath. The survey entailed systematic marking, draining, levelling of the bogs. A canal system was to provide for both drainage and transport. A portable rail system, based of movable wooden tracks, was designed. Special ploughs for bogland drainage were devised.

For most of twelve months, Edgeworth spent day after day, often for fifteen food-less hours at a stretch on the bogs of C. Longford. After this exhausting toil, he could confidently claim that the development of the Irish bogs was not only practicable but was economically viable and offered important employment prospect for the impoverished population of the country.

His work. Like several other precocious projects of his, failed to secure government support. In this instance, vested interests on the part of absentee landlords as well as of local proprietors conspired to thwart Edgeworth’s plans. But, he has been posthumously vindicated. A century later, a free Irish State gave reality to his dreams, following not only the spirit but also to methods and equipment and techniques. We should spare a thought for Edgeworth when we pass by Bord na Mona’s Installations at Lanesboro and elsewhere in the county.

A second area of Edgeworth’s vision gives equally impressive proof of his enlightened thinking, namely the sphere of education. He was influenced, in this domain, by the theories of Locke and Rousseau. His own writings though somewhat verbose and turgid, helped to diffuse new and more scientific approaches to education in the early eighteenth century.

His three volumes entitled “Practical Education,” published in 1798 drew upon the new empiricistic psychology to urge that education should depend upon natural associations of ideas rather than on rote memory; that spontaneous learning was preferable to coerced concentration; that teaching should proceed by teacher-pupil conversation rather than by cramming. The end-product of good educations he argued, would be, not the pupil who could mechanically reproduce facts, but the person who had “learned to generalise his ideas and to apply his observations and principles.” If the pupil can do this, he can be called educated, whether he can reproduce the facts of grammar, geography, or even Latin, or not. For he will desire better than merely knowing facts. In the subsequent business of life, he will out-distance the man “ who had only been technically taught, as certainly as the giant would overtake the panting dwarf, who night have many miles start of him in the race.”

Here again, as his biographer remarks, Edgeworth was more than a century ahead of his time. As Macadam annexed the reputation Edgeworth should have had in road-making, so Edgeworth lost to Montessori, Froebel, Pestalczzi and others the prestige he merited in the field of education.

His second book in this subject, “Practical education,” published in 1808, was less enlightened and less successful. But his contribution to the cause of education was not merely theoretical. He availed of his opportunity as Member of the Irish Parliament, convened in 1799, to introduce proposals “for the education of the peasantry and working part of the community in Ireland.” In his supporting speech, he declared, “the power of the sword is great, but the power of education is greater.” But, he urged, the state of education in Ireland was lamentably defective and only sweeping new legislation could remedy the situation. He proposed a building programme to provide one or more schools for each parish in the country. He advocated training and qualifications for teachers and inspection of schools.

The most notable and praiseworthy feature of Edgeworths educational plan was that it envisaged equal educational opportunity, at primary school level, for Catholics, with safeguards for their religious beliefs and total exclusion of proselytism. School books were to be approved by the clergy and separate religious instruction for Catholics to be provided by the clergy. It was to be many years yet before the British government and the Irish ascendancy were to be ready to enact such tolerant ideas into law and practice. Edgeworth had a different conception from Davis of the relationship between education and freedom; but he agreed with him on the importance of education for the nation’s good. He considered the education of the people “ to be of greater and more permanent importance than the union or than any merely political measure could prove to his country.”

If Parliament failed to adopt his proposal, Edgeworth would at least make a beginning with his own estates. He founded, in Edgeworthstown, in 1816, a school for boys, which was open to Catholic and Protestant boys alike, and educated poorer and richer children side by side in the same benches. The better-off boys were boarders, with separate dormitory quarters; but the mingling of social classes during class hours was a distinctive feature of the school. The pupils went out to their respective churches for worship and their own clergymen came in to teach then religion during school hours. Edgeworth arranged for a “post-primary” section in the school, where boys might remain on after the school-leaving age to learn book-keeping, mechanics, commerce, and elementary science. He also provided a playground, believing that games too had their place in education.

This remarkable experiment was unfortunate in its immediate direction. Edgeworth’s son, Lovell, who was put in charge of it, proved inefficient, improvident and bibulous, and soon ruined a noble and pioneering educational project. But it lasted long enough to justify Edgeworth’s own boast: “Edgeworthstown is a village remarkable for the health and longevity of its inhabitants. As to religion and moral education here, happily the ministers of both the Protestant and Catholic religion are free from bigotry and live on the best of terms with each other without the slightest mutual jealousy.”

The liberalism, of Edgeworth found expression in his political stances, as several courageous speeches testify. The years after ’98, he wrote: “To justify myself to the Orange Party here can only be done by wearing orange ribbons and becoming a member of the Orange Lodge-a thing I would never be induced to do.”

The ’98 rebellion was followed by a wave of orange fanaticism, bigotry and bitter sectarian reprisals. These so disgusted Edgeworth that he contemplated leaving Ireland for good. He wrote at this time “I have lived in Ireland for no other motive than a sense of duty and a desire to improve the circle around me. I shall lose about £10,000 sunk in the country by removal, but I shall live the remainder of my life amongst men instead of warring savages.”

These words do something to offset the Edgeworths’ attitude to the Irish insurgents at Ballinamuck. In fact Edgeworth was in greater personal danger from Orange loyalists at the time of the Ballinamuck battle, than he was from the Irish rebels. The leader of insurgents personally guarded the entrance to Edgeworthstown House and refused admittance to any of his men. The Orange yeomanry in Longford, knowing Edgeworths’ scorn for their bigotry, and his detestation of their politics, drove him out of the town with stones and staves.

The fullest expression of Edgeworth’s political liberalism was given, a decade before ’98, in his address to the Irish Volunteers. In this address, he demanded equal civil rights for Catholics. He called for the emergence of a yeomanry “which will diffuse liberty and industry throughout every class of the inhabitants of Ireland.” He predicted that the aristocracy would come to bless the hour that turns their ambition from a sordid scramble for titles and places to the solid happiness of serving an industrious and prosperous people.” His political testament may be found in the same address, “For myself, I have no interest to serve, no private pique to gratify, nor have I any view in offering you my advice, but what every Irishman would be proud to avow-the liberty and glory of my country.”

Edgeworth’s patriotism was qualified, his nationalism conditioned by the inevitable ambivalance of the colonist. But it would be narrow-minded and chauvinist to exclude such men as Edgeworth from their place in the pre-history of modern Irish nationalism, and it would be unhistorical to define patriotism in such a way as totally to refuse the term patriotic to a man whom the British loyalists in ’98 regarded as a renegade and suspected of treachery.

Edgeworth died in 1817. Five days before the end he wrote calmly about his impending death. “If a careful retrospect be made of former life; if faults which we have committed strike us with regret, and if we do sincerely believe that we should avoid them were we to live over again; and if upon the whole we feel the internal conviction that we have exerted our faculties in the exercise of our domestic duties and, in so far as it has been in our power, for the public good, I do believe the descent to the grave, if we can escape bodily pain, may resemble sinking into deep sleep.” Maria wrote that his last words were “I die with the soft feeling of gratitude to my friends, and submission to God, who made us.”

1743 – 1773. Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s first wife and motther to Maria. He eloped with her to get married but it wasn’t a happy marriage.

1751 – 1780. Second of Richhard Lovell Edgeworth’s wives, he was in love with her before his first wife died. She was a noted writer and educationalist in her own right.

1753 – 1797. Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s third wife, and sister to his second wife Honora. Gave him five sons and four daughters.

1769 – 1865. Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s fourth wife, gave her husband six children and outlived him by forty-eight years.

The best way to keep in touch and to be aware of our events

Don’t forget to confirm your subscription in the Email we just sent you!

Please pre-book your visit over Christmas at least 24h in advance via Email or Online booking.

MondayClosed

Tuesday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Wednesday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Thursday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Friday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Saturday11:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Sunday11:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Adult €7.50

Children 10 to 16 €3

2 Adults & 2 Children €15

Adult is 16 years+

Family Ticket is 4 family members together

Children under ten are free but must be accompanied by an Adult

The Maria Edgeworth Centre is operated under the direction of the Edgeworthstown District Development Association (EDDA) – a Not for Profit Voluntary Community based registered charity Reg:223373. Registered Charity Number 20101916

© 2023 Maria Edgeworth Centre – All Rights Reserved

On the 17th of August 2024 as part of Heritage Week, with support from the County Heritage Officers, the Heritage Council, Longford County Council Libraries, Archives, Arts and Heritage,

IMMA, OPW and the Computer and Communications Museum Ireland on the NUIG Campus,

Ray Jordan and volunteers from the Maria Edgeworth Centre aim to simulate Edgeworth’s 1803 transmission by telegraph.

Click the link below to learn more or to register to attend either in person or via Zoom.

Join us for this recreation of a key moment in the history of communications