Today, March 1st, 2024, Catherine Martin T.D., Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport, and Media, as well as Chair of the National Famine Commemoration Committee, has announced that this year’s National Famine Commemoration will be held in Edgeworthstown, County Longford, on Sunday, May 19th, 2024.

The public ceremony, set to be broadcast on the RTÉ News Now channel, offers a poignant opportunity for the communities of Longford and neighbouring counties to pay homage to those who endured the hardships of the Great Irish Famine, whether perishing or seeking refuge abroad.

This marks the inaugural occasion of the State Commemoration taking place in County Longford. The event will uphold tradition with military honours and will conclude with a solemn wreath-laying ceremony, honouring the memory of all those affected by the famine’s devastation.

-Taken from an article written by County Archivist Martin Morris and published in the book 'o theach go teach' a history of Edgeworthstown published in 2003 by the Edgeworthstown Historical Group.

In the period of the ‘Great Famine’ (1845-1851), the civil parish of Mostrim consisted of thirty-four townlands and the town, covering just over 10,943 acres.

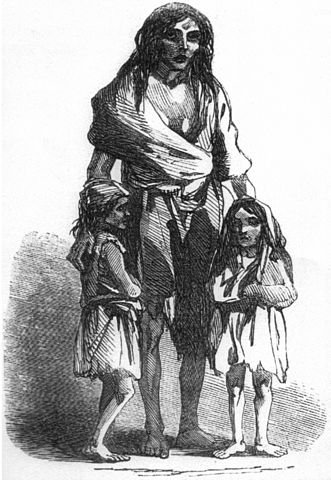

The census of 1841 revealed that it had a population of 4,933, of whom 864 (or 21%) lived in Edgeworthstown itself. As the population generally was increasing quite rapidly, we may assume that by 1845, the parish would have had over 5,000 people. It can also be assumed that in common with the rest of Ireland, those in the parish most dependent upon the potato crop were the small farmers, the cottiers and the labourers. Frequently, the distinctions between those three groups were very blurred, but the rapid rise in population from the beginning of the nineteenth century was especially evident among them.

Constable Peter Byrnes reported from the Famine in Edgeworthstown on 28 May 1846 : he stated that there had been 300 acres sown in 1844 and 280 acres in 1845. However, the partial failure of ‘45 meant that in 1846, there were 208 acres planted, or almost one third less than two years earlier. During the autumn of 1846, the local relief effort expanded in response to the worsening situation. On 4 September, a meeting of the clergy, landowners and farmers of Mostrim was held in the Market House in Edgeworthstown under the chairmanship of Michael Pakenham Edgeworth (another of Maria’s half-brothers). It was decided that subscriptions be collected to purchase Indian meal and other foodstuffs. A committee was appointed with the following members: Francis B. Edgeworth, Rev. Thomas Gray P.P., Rev. J. McNally C.C., Mr. Cowen, Surgeon Dobson, Mr. Tynan, Mr. Rhatigan, Mr. Kenny, Mr. Green, Mr. James Kelly, Mr. Duffy and Mr. McKeon. . The most important factor in determining the course of the Famine in any area was the response of the local landlord.

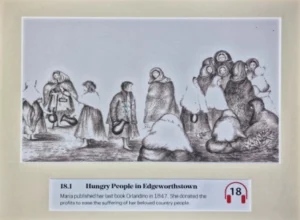

If a landlord was genuinely interested in the welfare of his/her tenantry, then their actions would quite literally make the difference between life and death. The people of Edgeworthstown were fortunate to have, living in the ‘big house’ at their time of acute need, a lady of action – the novelist Maria Edgeworth (1767-1849). On 30 January 1847, she completed a questionnaire for the Society of Friends Dublin Central Relief Committee which provides us with a reasonably clear impression of conditions at that point. She estimated the population (presumably of the entire parish) at 5,000, of which 3,000 required relief. She worked with her stepmother, Frances Beaufort Edgeworth, to distribute food and clothing to the poor in the area[16].

Edgeworth did not believe in giving relief indiscriminately – it was important for the poor to work for themselves as far as possible, and that included women and girls. She suggested, in a letter to Dr. Joshua Harvey of the Society of Friends, that a small sum of money could procure materials for women for such activities as needlework and knitting. Harvey’s committee granted £30 towards the distribution of soup and a further £10 for providing female employment.

As a famous author, Edgeworth had friends and acquaintances in many places and she sought the assistance of some of them. One, Miss Ryan in Cincinnati, Ohio, persuaded the relief committee there to spend the balance of its funds – $180 – on cornmeal to be sent to her. She also received contributions from, among others, Professor Ticknor of Harvard University who had visited Edgeworthstown with his wife in the 1830s, and from ‘about thirty young people and children of Boston’ from their pocket money. An American ship’s captain named Robert Bennett Forbes later wrote that $280 and 100 barrels of supplies were sent from Boston to Edgeworthstown. The most lasting action by Edgeworth in her endeavours to alleviate the suffering around her was the writing of the novel Orlandino, a children’s story published in 1848, the proceeds from the sale of which would go to famine relief.

Regarding mortality in the Edgeworthstown area, Maria informed her sister Honora Beaufort, in a letter of 8 May 1847, that it was ‘not so much as a third’ above the normal level. However, the writer did not always remain in the comfort of her house and listen to the tales of others. We have an extraordinary eye-witness account from Biddy Macken of Pound Street, who worked as a servant to the Edgeworth family and, in 1912, recounted some of her poignant memories of the years of the ‘Black Praties’ to Richard Hyland N.T.

Then a teenager, Biddy recalled: “I went around with her (Maria) from house to house in this town and far outside it carrying a big basket filled to the brim with food. No house was passed by Maria without calling. Not only food was given but turf and warm clothing purchased in the town. She was barely able to walk then and had a short “cruben” stick to help her along. The “favor” was in a lot of houses but Maria did not mind. When she visited the poor she was always cheerful and had a way of “making them laugh”. She was short of breath often when we were going up that hill (Pound Street) and often she had to sit down weary and tired in the “parlour” when she got home.