In the late eighteenth century, Edgeworthstown in County Longford, Ireland was the site of experiments in a cutting-edge communications technology – Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s Optical Telegraph.

In the old days people used smoke signals, beacon fires, flags or arms as ways of early communication. However, Richard Lovell Edgeworth refined these.

Maria Edgeworth writes to her aunt Margaret Ruxton. Edgeworthstown, April 11, 1795:

“My father and Lovell have been out almost every day, when there are no robbers to be committed to jail, at the Logograph. This is the new name instead of the Telegraph, because of its allusion to the logographic printing press, which prints words instead of letters… My father will allow me to manufacture an essay on the Logograph, he furnishing the solid materials and I spinning them.”

The first use of the optical or semaphore telegraph – then known simply as the telegraph – was in revolutionary France. They used visual signaling apparatuses with moving arms set on top of towers to relay messages across long distances at astonishing speed.

Despite the debut of a line of these machines between Paris and Lille, Richard Lovell Edgeworth began to develop his own system soon after, in 1794. It was his dream to construct a communication network of telegraph stations to cover the whole of Ireland.

In August of that year, he demonstrated his optical telegraph by ‘conversing’ over a distance of 12 miles between Edgeworthstown and Pakenham Hall (now Tullynally Castle), the seat of Lord Longford. The ‘Tellograph’ was born. Therefore Edgeworthstown in County Longford got its own place in the history of telecommunication.

Now a team led by Ray Jordan wants to bring Edgeworth’s 1794 connection back to life.

Ray’s background is as an engineer in Posts and Telegraphs at Telecom Eireann. In 1994 he became interested in the possibility of Telecom Eireann actually simulating Edgeworth’s semaphore system between Dublin and Galway.

Unfortunately, shortly after that, he retired and the project was abandoned. It didn’t resurface in his mind until 2023. At that time, he became interested in Edgeworth again. Recently, Ray wrote an article published in Ireland’s Eye on the subject of Richard’s earlier 1794 Semaphore event. He realized that it would be a far simpler task to replicate the 1794 demonstration than the 1804 Dublin Galway link.

Ray’s team have constructed a replica of the Edgeworth telegraph and trial runs are soon to begin.

A replica telegraph constructed using materials and methods that would have been available in 1794

The choice of the name ‘Logograph’ and later ‘Tellograph’ was strategic – because it distanced Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s invention from the one that was used in France. Obviously this was a response to the political climate of the 1790s, when anti-Gallic sentiment ran high amongst the ruling class. As the decade progressed, rapid intelligence to counter the threat of French invasion – and Irish rebellion – were the telegraph’s main selling points.

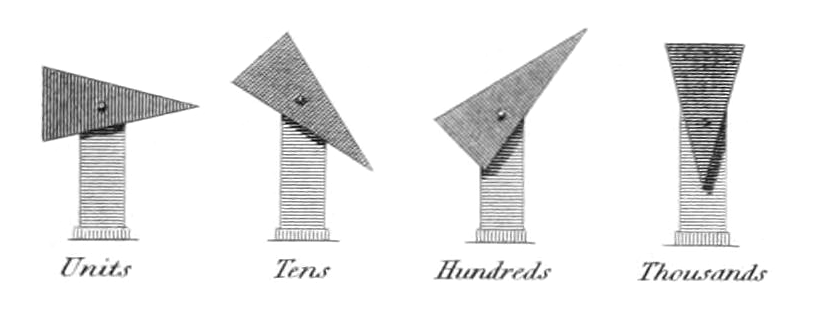

The design of Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s Optical Telegraph used rotating pointers in the shape of an isosceles triangle. The pointer would be moved to different positions indicating numbers from 0 to 7 – in the picture, the code is 2314. Initially, he wanted each station to have four of these indicators in a row, so that a multi-digit code could be sent all at once. However, this was thought too expensive, as it required more personnel to manually operate the machines. As a result, a single pointer system was introduced, where a series of up to four numbers would be ‘written’ for each message.

John Farey, Jr., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As well as telescopes to see the distant stations, the system required a codebook. Letters, words, and predefined questions and answers were assigned to the numerical codes. In later years, Maria Edgeworth and other family members were tasked with writing the codebook, or telegraphic ‘Vocabulary.’ A specimen of code, held at the National Library of Ireland, has messages such as ‘Any appearance of fire signals,’ and ‘Can the Yeomanry be ready to march at an hour’s notice.’

Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s copy of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary offers a glimpse into the design process of the codebook. It has numerical annotations in the margins, showing the words that were chosen for inclusion.

Annotations in the copy of Johnson’s Dictionary. On display at the Maria Edgeworth Centre

Despite its advantages, the optical telegraph did have its share of challenges and limitations. It could only transmit messages as far as the visibility of the signaling stations allowed, hence making long-distance communication beyond a certain range difficult. Adverse weather conditions presented a significant problem; fog, rain, and snow could render the system ineffective. Consequently the system’s reliance on clear visibility made it vulnerable to the unpredictable nature of the Irish weather.

When Richard Lovell Edgeworth eventually succeeded in having a line established, it also became clear that the system was highly prone to human error. A single digit wrongly transmitted could result in failed communication and confusion. But the greatest obstacle to the establishment of the telegraph was the reluctance of the government to support it.

In collaboration with her father, Maria Edgeworth wrote letters to government officers and essays to promote the telegraph. After all, the main problem was trying to convince a reluctant Dublin Castle of the need for the expense.

The demonstration of Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s Optical Telegraph between Edgeworthstown and Tullynally was the first of many. Another example was an experiment where two of his sons communicated across the Irish Sea between Donaghadee and Port Patrick.

This event was publicized in the Northern Star (the newspaper of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen). The publication of a poem celebrated the occasion.

LINES ADDRESSED TO RICHARD AND LOVEL EDGEWORTH, ESQRS.

Who actually conversed across the channel between Donaghadee and Portpatrick, by means of the Telegraphe.

“Basaltic coasts, and giant walls proclaim

Majestic nature in great extreme,

And your effort, brave EDGEWORTH, doth unite,

A grand display of genius and of light,

Adding new lustre to Hibernian fame

Which will immortalize thy worth name.

Quick at the voice of fortune genius smiles,

And joins the Patriot hands and sister Isles.

Superlative contrivance! That did raise

The Telegraphe and speak across the seas!

Holding free converse on a distant shore,

What ne’er was aimed at by man before.

Hov’[r]ing in air the kindred tidings flew,

By thy machine presented to our view;

A sight so lovely, surely does express,

An image of thy name—That’s Loveliness.*”

Donaghadee, August 29, 1795.

*One of the Gentlemen’s christian name is LOVEL.”

(From the Northern Star, No. 383, 31 August – 3 September 1795)

Finally, in 1803, permission was granted for the construction of a line of Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s Optical Telegraphs between Dublin and Galway.

A map of possible locations of the signalling stations, courtesy of Ray Jordan

Nevertheless, his ambition to have a whole network installed across Ireland never came about. The line of Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s Optical Telegraphs between Dublin and Galway, completed in 1804, was decommissioned within a year and never re-established.

By bringing the 1794 experiment back to life, we hope interests might be piqued and clues might be uncovered to a hidden history of Irish telecommunications.

Written by Dr. Joanna Wharton, Research Associate of the University of York, Ray Jordan, John McGerr and Janine Roder