The third member of the Edgeworths we meet is Henry Essex Edgeworth, who was born in 1745 and died ages 62, in 1807, at the height of Napoleon’s campaign against Russia.

He was born at the Rectory at Edgeworthstown, the son of the Rector, Robert Edgeworth who was a first cousin of Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Maria’s father. He was a great-grandson of Archbishop Ussher, distinguished Anglican scholar-Archbishop of Armagh. His grandfather had been Rector in the same vicarage before his father.

By a decision of remarkable courage and integrity, Robert Edgeworth became a Catholic, as the result of a long process of prayer and reflection and study of the Bible and the Fathers of the Church. One of the dominant reasons for his decision was a growing conviction of the biblical truth of the Catholic doctrine of the Real Presence. It was while preaching on “the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper” from the pulpit of his Parish Church, that his conviction of the truth of the Catholic Church became final. He broke down in the middle of his sermon and could not continue. He came down the steps of the pulpit and was never able to bring himself to mount them again. His reception into the Catholic Church followed soon after.

This was in 1749. It was henceforth impossible for the ex-Rector and his family to remain in Ireland. He went to France and settled at Toulouse. A modest revenue followed his annually, from a small property at home called Firmount. Later, when his son, now fully gallicised, found that Frenchmen had difficulty in pronouncing the name Edgeworth, he borrowed the “Firmount,” in the French form, “Firmont,” and called himself Henri Essex de Firmont.

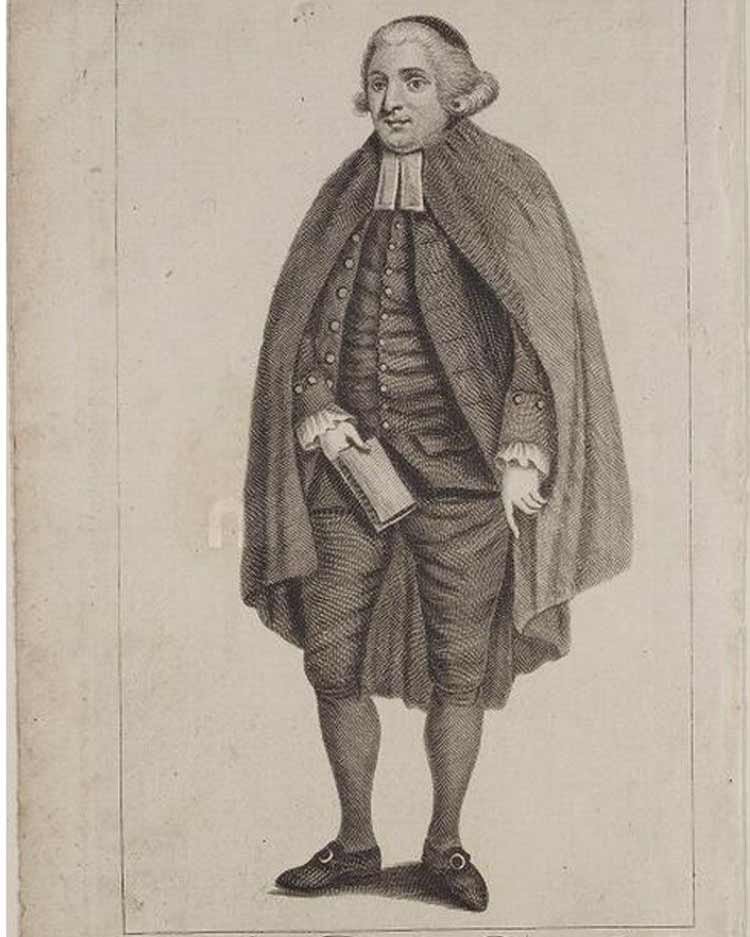

Henry Essex grew up as an ordinary French Catholic boy. Educated by the Jesuits in Toulouse and later at the Sorbonne in Paris, he felt a vocation to the priesthood and was ordained for the diocese of Paris. He devoted himself with ardour to pastoral work among the poor of the Paris slums. He continued to reside in the seminary of the Missions Etrangeres de Paris on the Rue du Bac. But devoted himself to spiritual direction and work of the confessional. He rapidly became much sought after as spiritual director and confessor.

His name became known at the court, and in 1791, on St. Patrick’s Day, he was summoned to the Royal Palace of the Tulleries and asked to become confessor to the sister of Louis XVI, Madame Elizabeth. From now on the Abbe Edgeworth or as he was better known in France, the Abbe Firmont, was to be closely identified with the fortunes and fate of the French Royal Family in the most tragic moments of their history.

When Louis XVI was in prison, it was the Abbe Edgeworth whom he summoned to give him spiritual ministration. The Abbe’s letters and notes are among the most precious records of the ill-fated monarch’s personal reactions to the blows of the Revolution. When he came to the King’s side in his prison cell, the King said: “Now, sir, the great business of my salvation is the only one which ought to occupy my thoughts. The only business of real importance! What are all other subjects compared to this?”

The Abbe accompanied Louis XVI to the scaffold. He has left to history an eye-witness account of the last moments of Louis Seize, or Citizen Capet, as the revolutionaries called him as he waited for the guillotine to fall. The King bore himself erect with remarkable fortitude. He declared that all his happiness and strength in this extremity came to him from his religious principles. He requested the revolutionary guards to respect and spare “this good man,” the Abbe Edgeworth. He died protesting his innocence of the crimes laid to his charge, and praying that his blood might never be visited on France.

The Abbe, his clothes drenched in the King’s blood, was able to slip away unnoticed amidst the frenzied crowd. He may not have said the words: “Fils de Saint Louis, montez au ciel.” “Son of Saint Louis, go up to Heaven,” – but the words express the feelings the Abbe from Edgeworthstown would have had as he slipped through the revolutionary crowd in the Place de la Revolution, which had until a few months before been called the Place de Louis XV and was later to be called, more hopefully, Place de la Concorde.

The Abbe escaped from Paris and experienced exile in England, Germany, Russia and finally Poland, in the company of two survivors of the French Royal Family. To whom he remained loyal to the end.

In 1807, during Napoleon’s Russian campaign, they were at Mitau in Poland. Twenty-three soldiers from Napoleon’s army were brought to hospital there in high and virulent fever. The armies of Napoleon were, in the Abbe’s circle, regarded as ministers of evil. But for the Abbe the soldiers were only souls to save, Christians in need of priestly help. As soon as he heard of their presence, regardless of the danger of infection, the Abbe went and ministered to their spiritual and material needs. He caught the fever, but continued day and night to bend over their bedside. After a few days he could struggle on no longer. He collapsed after Mass one morning and died a few days later. His epitaph in the cemetery at Mitau commemorates “the Very Reverend Henry Essex Edgeworth of Firmont, a priest of the Holy Church of God, who, pursuing the steps of our Redeemer was an eye to the blind, a staff to the lame, a father to the poor, and a consoler to the afflicted.”

The best way to keep in touch and to be aware of our events

Don’t forget to confirm your subscription in the Email we just sent you!

Please pre-book your visit over Christmas at least 24h in advance via Email or Online booking.

MondayClosed

Tuesday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Wednesday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Thursday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Friday10:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Saturday11:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Sunday11:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Adult €7.50

Children 10 to 16 €3

2 Adults & 2 Children €15

Adult is 16 years+

Family Ticket is 4 family members together

Children under ten are free but must be accompanied by an Adult

The Maria Edgeworth Centre is operated under the direction of the Edgeworthstown District Development Association (EDDA) – a Not for Profit Voluntary Community based registered charity Reg:223373. Registered Charity Number 20101916

© 2023 Maria Edgeworth Centre – All Rights Reserved

On the 17th of August 2024 as part of Heritage Week, with support from the County Heritage Officers, the Heritage Council, Longford County Council Libraries, Archives, Arts and Heritage,

IMMA, OPW and the Computer and Communications Museum Ireland on the NUIG Campus,

Ray Jordan and volunteers from the Maria Edgeworth Centre aim to simulate Edgeworth’s 1803 transmission by telegraph.

Click the link below to learn more or to register to attend either in person or via Zoom.

Join us for this recreation of a key moment in the history of communications