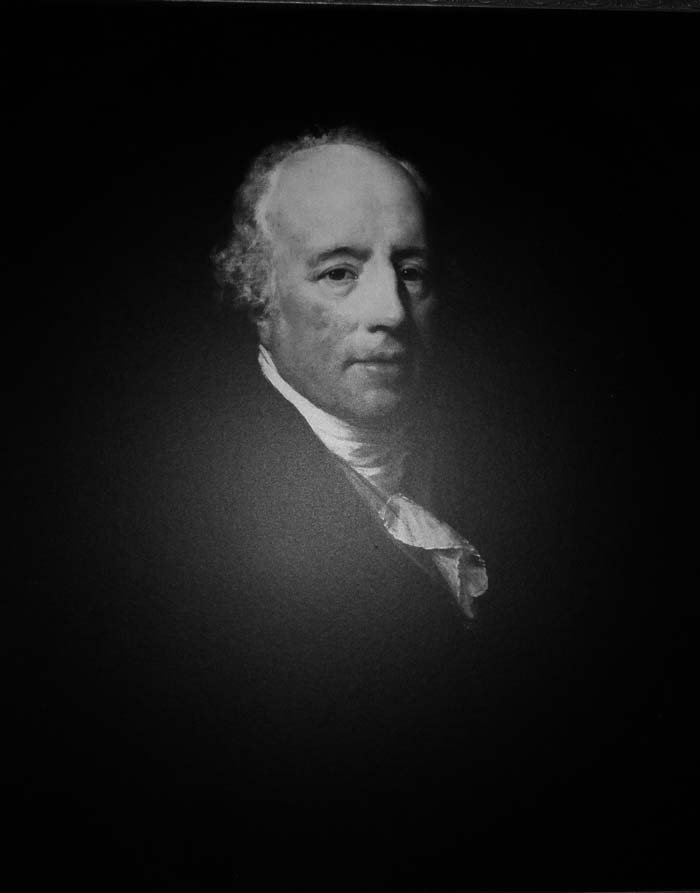

Richard Lovell Edgeworth could be regarded as a major figure in the history of education. His significance should not be overlooked, especially as he was writing at a time when representatives of tradition, like Knox and William Barrow, favoured the classical curriculum and its aims. It was innovators like Edgeworth who were prepared to try out new ideas. Edgeworth was non-sectarian in his outlook, and at a time in Ireland when sectarianism caused insurmountable difficulties, he did not favour the teaching of religion in schools. To this end, he established a multi-denominational school at Edgeworthstown in 1816. While the school suffered financial difficulties, with the help of Maria it remained open until 1834.

In the spring following the rebellion of 1798 the Irish House of Commons considered and rejected a bill which contained a radical plan for the education of the poor in Ireland. It has been held by historians of Irish education that the contents of the bill were subsequently lost and that the reasons for its rejection would never be known. Recently, however, a draft of the bill has come to light amongst the Edgeworth family papers and it is here being published for the first time. From this, and from the report of the debate in the Dublin Evening Post, a missing piece of the history of Irish education can be reconstructed.

The Commissioners for Education visited the school in 1826. Their report was very favourable: according to Maria Edgeworth, writing in 1839, ‘… they examined and saw the working and playing of the school and had all the opportunities that could be given of observing for themselves and of privately cross-questioning pupils and masters, clergymen and priest’. They found ‘proof of the possibility in practice of what had been deemed by many absolutely impracticable, the educating of Protestant and Catholic children together without injury or inconvenience of any kind’. It is a pity that the school’s success did not lead to the establishment of any other enterprises of a similar nature. Perhaps those who forged the 1831 National School System had the Edgeworthstown school in mind when they adopted an approach to education in which the teaching of religion should not play a part during school hours.

Edgeworth with his second wife Honora and daughter Maria, he decided to embark on a systematic course of education for his growing family (he had twenty-two children in all, from four different wives), he left dogma and primitivism behind, believing that a child’s personality and knowledge are the result of his upbringing and schooling only. Edgeworth and his wife, from 1778 onwards, would make notes on the children’s progress, and those would provide the empirical basis for steering their course of study in particular directions. This first-hand experience of the education of children provided the material for the very innovative educational treatise Practical Education, published in 1798, the joint work of Richard Lovell and his daughter Maria. They state in the preface: “To make any progress in the art of education, it must be patiently reduced to an experimental science […] we lay before the public the result of our experiments, and in many instances the experiments themselves.” As a Member of the last Irish Parliament, and a member of the committee of the Board of Education, Edgeworth made a speech on the education of children from the lower classes, which was reported in the press.

In the long term, Practical Education was a very influential educational treatise, but initially it was well received only in liberal circles, because 1798 “was not a year for welcoming progressive books”, with the French Wars going on and the general suspicion towards advanced ideas of any kind. Apart from its empirical approach to learning, Practical Education was remarkable for the breadth of topics included in the curriculum – traditional subjects like ancient literature, chronology and history, but also modern subjects such as chemistry and mechanics; the book also discussed moral education.

Hedge schools (Irish names include scoil chois claí, scoil ghairid and scoil scairte) were small informal illegal schools, particularly in 18th- and 19th-century Ireland, designed to secretly provide the rudiments of primary education to children of ‘non-conforming’ faiths (Catholic and Presbyterian). Under the penal laws only schools for those of the Anglican faith were allowed. Instead Catholics and Presbyterians set up highly informal secret operations that met in private homes.

Historians generally agree that they provided a kind of schooling, occasionally at a high level, for up to 400,000 students by the mid-1820s.

While the “hedge school” label suggests the classes took place outdoors (next to a hedgerow), classes were normally held in a house or barn. Subjects included primarily the reading, writing and grammar of the Irish and English languages, and maths (the fundamental “three Rs”). In some schools the Irish bardic tradition, Latin, history and home economics were also taught. Reading was often based on chapbooks, sold at fairs, typically with exciting stories of well-known adventurers and outlaws. Payment was generally made per subject, and bright pupils would often compete locally with their teachers.

It was a letter from Chief Secretary for Ireland Edward Stanley in 1831 that was to provide the impetus for a new National School System in Ireland. The Stanley Letter echoed Richard Lovell Edgeworth’s failed 1799 Bill as well his general thoughts on aspects of Education.

Comments on the Stanley Letter from the Irish National School Trust website.:

The Stanley Letter remains today the legal basis of the National School system. It has not been replaced by any legislation specifically for National Education.

The core principle of the Stanley Letter is that children of all religions should be taught together in the same school.

Public funding would only be provided for schools where there was no hint of proselytism (attempting to convert children to another religion).

Primary education for all children should be free.

The Stanley Letter envisaged the existence of private faith schools – but, if schools wished to subject themselves to the National School system (and the funding that accompanied such a system), they would have to subject themselves to the control of the Commissioners for National Schools (the Rules for National Schools).

The Stanley Letter envisaged that the State (through the Commissioners) would exercise complete control over the schools. Such control was transferred after Independence to the Minister for Education.

There was to be local funding for the building of the schools, and for the maintenance of the buildings thereafter.

Religious instruction would be carried out by clergy of the various religious denominations.

That Letter was also the reason that in 1840 the schoolhouse on the Ballymahon Road in Edgeworthstown was first opened with Maria Edgeworth as one of the sponsors. It has been an active part of Education in Ireland as a National School and Adult Education Centre and now is home to the Maria Edgeworth Centre.

This article has been compiled from a variety of sources and if you would like to read more on this subject then please visit the links below

Stanley Letter 1831 Link

http://irishnationalschoolstrust.org/the-clontarf-report/4-2-the-stanley-letter-1831/

Article on Hedge schools

http://irishnationalschoolstrust.org/the-clontarf-report/4-2-the-stanley-letter-1831/

Article on RLE Education bill

http://www.erc.ie/documents/vol13chp2.pdf

Source for info on RLE

Isabelle Bour, « Richard Lovell Edgeworth, or the paradoxes of a “philosophical” life », Études irlandaises [En ligne], 34.2 | 2009, mis en ligne le 30 juin 2011, consulté le 22 août 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/1600; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesirlandaises.1600